Bookstores: Why should we keep going back?

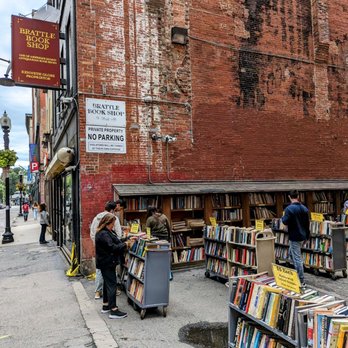

The Brattle Bookshop is not inconspicuous by any means. It announces itself first, with a parking lot full of carts stocked with books, then two signs: one a giant book, hung to the side of the building, and one a giant pencil, positioned horizontally across the front. Inside, the shop is cozy and quaint, with tight rows of shelves and walls full of antique posters.

On the other hand, Trident Booksellers & Cafe is easier to miss. Packed in a small brownstone on Newbury St., it has a modest exterior that betrays its rich, whimsical space. Two narrow windows aptly announce “BOOKS” and underneath, “Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner.”

Besides their appearance, the two stores work in vastly different ways. Brattle Bookshop largely sells used books, which Nicole Reiss, manager of twenty-six years, says are bought from “people who are moving, downsizing estates,” and come from “all over,” from Chicago to New Hampshire.

Because Trident is not a used bookstore, it sources directly “from a variety of major publishers and minor publishers,” according to the manager, Jack Fox. This sourcing method is something Fox takes advantage of; for instance, Fox enjoys the “advanced reader copies,” or soon-to-be published books that he gets early access to.

Even with their sourcing differences, the managers at both bookstores seemed to agree on several topics. Namely, the community that bookstores provide.

Something that keeps Fox going as he manages the bookstore is “the sense of community that [he has] with the literary scene in Boston.” By running a program called the writers’ room, Fox can interact with groups of people who are “huge lovers of… our books and are writers themselves.”

“I think that writing and reading have this reputation as being solitary pursuits,” Fox added, “when in reality, anything that is fundamentally artistic, a large part of it is going to be based on your community.”

Reiss carries a similar view on the power of bookstores to bring people together.

“We’ve had people get engaged here,” she said, “We’ve had people meet their significant others. We’ve had weddings. But also people who have met their best friends.”

Both managers also shared kindred opinions on the future of bookstores, and what it means to walk into a store instead of going online.

When asked why bookstores mattered, both agreed that a physical environment is crucial.

“People want to hold a book,” Reiss said, “…you come into a bookstore, and it smells like a bookstore…you’re not going to get that from being online.”

In the same vein, Fox said, “walking through a physical space is inherently very different from browsing online…You’re getting a curated experience from local people you can talk to.” The “human touch” is an important part of bookstores that “people want,” Fox added.

Reiss and Fox had their own two cents to add on the value of choosing a bookstore over surfing the web.

“[The algorithm] doesn’t care about you,” said Reiss simply, “Booksellers do.”

“Just walking through the physical space allows you to be exposed to things that you’d never see in a curated algorithm environment,” said Fox. “So much of browsing in an online space is about what the algorithm has selected for you. And there’s no algorithm here.”

Instead of an algorithm, Fox continued, bookstores are a conglomeration of human decisions.

“It’s books that you think are going to sell or that people want to buy or want to read, based on what meets the community, local authors, local readers, who are deciding what is on the shelves and what isn’t,” said Fox. “And I think that that’s really valuable. It provides a lot of exposure to ideas and literary and artistic creations that you wouldn’t otherwise have the opportunity to see.”