The Victims Without Justice: We Need to Talk About Cold Cases

In Massachusetts, there have been 10,128 homicides from 1965 to 2022 but only 61% have been solved, leaving 3,989 unsolved. Why does this happen? Why does our law enforcement just give up on a case? This is something I wonder a lot about. Do they get too busy? Is it too challenging to solve? Or do they just give up? All of these are real reasons that we have all the cold cases we have today along with some that have had the victims’ advocates die or had files destroyed. But a case going cold does not mean it should be forgotten. The victims were real people with lives just like us; their stories have not been completed. More people need to be aware of cold cases because a witness could be withholding information, a murderer could be walking free, and DNA technology today is better than it was in the past.

But first, what is a cold case? Cold cases are cases that have not been fully solved nor are being currently investigated, or, in other words, they’ve gone cold. Cases stay cold until they are investigated again, then they are considered open cases. But some cases stay cold for a very long time like the Black Dahlia murder. Before the authorities were able to solve the case, everyone who knew the victim and potential witnesses had died out, making it impossible to give testimonial evidence. But a case being difficult to solve doesn’t mean we should just give up or forget about the victims. In addition, there is also a possibility that the perpetrator is still out there, putting society in danger. But if most cold cases are people from decades ago, they shouldn’t matter to us, right? Wrong. All cold cases, even ones from decades ago, are still important.

For every crime that happens, there is almost always a witness or someone who knows something. But sometimes these witnesses don’t come forward to share what they know, usually because they want to protect themselves or someone they love. When the case goes cold, these witnesses have to keep their secrets for many years and some keep their secrets till just before they die; these are known as deathbed confessions. But how can we get people to share what they know before their death? Let’s take Tara Grinstead’s case for example; Grinstead was a Georgian school teacher before her untimely disappearance in 2005. The case went cold after many dead ends until in 2016, Payne Lindsey with the podcast Up and Vanished started his own investigation. In his search for leads, Lindsey talked to people from where Grinstead was from, and as the podcast grew in popularity, finding people who were willing to talk became easier. Lindsey told Rolling Stone that “people grew more comfortable telling [him] what they thought or had seen or had heard” and that the podcast began to “generate new leads.” The podcast was a wake-up call and six months after the first episode, someone called in a tip to Georgia’s Bureau of Investigation (GBI) on a man named Ryan Duke. Ryan Duke and a friend were eventually charged in her case. While I don’t expect everyone to make a podcast dedicated to solving cold cases, Lindsey’s dedication to getting people in Ocilla, Georgia to talk about this case again resulted in the case being solved.

Has anyone ever told you that “everyone walks past an average of 36 murderers in their lifetime” as a fun fact? Well, with cold cases, that could very much be true. When we think of unsolved cases we might forget sometimes that for every unsolved case, there is a murderer walking free, and potentially continuing to commit crimes. We see this realization in the case of one of the most famous killers, Dennis Rader, also known as BTK, who terrorized the city of Wichita, Kansas from 1974 to 1991, committing a total of ten confirmed murders. After 1991, Rader went quiet for years until 2004, when the Wichita Eagle published an article for the 30th anniversary of Rader’s first killing. This prompted Rader to start writing letters, taunting the local police to arrest him. The letters ended up giving the police enough clues that led to Rader’s arrest the year later. When a serial killer stops their killing sprees, usually the consensus is that they have died or gone to jail for another crime, which is usually a comfort to the families of the victims and society because they can no longer terrorize society. But, when they pop up again, it brings up so many questions. Where had they been? What had they been doing? It also means that while the families were grieving over their loved ones for all these years and hoping the murderer was in jail or dead, they had to find out that during their sorrow, the murderer was walking free and enjoying their life. Luckily, in this case, Rader was brought to justice. We cannot ignore the thousands of other criminals who are walking free because law enforcement didn’t make a good enough effort to close their cases.

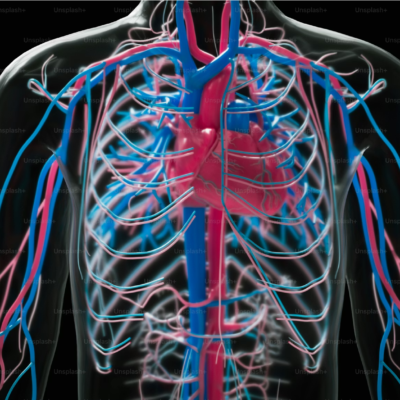

We have a much better chance of solving a cold case now than investigators did years ago. For example, let’s take it back to another one of the most famous serial killers, Joseph James DeAngelo. DeAngelo, also known as the Golden State Killer, terrorized from 1974 to 1986 in California. In that time he committed at least 13 murders, 51 rapes, and 120 burglaries. He was never caught and the cases went cold until investigators plugged DNA found at crime scenes into the genealogy database and found a match. He was finally arrested in 2018. Genealogy databases are commonly used today to solve cold cases where there is no other hope to solve them using physical evidence. Law enforcement uses these databases to solve crime in a few ways but the most common way is STR (short tandem repeat) profile matching which, according to the National Library of Medicine, compares “STR profile data generated from crime scene samples” with the STR profile of a person of interest or data stored in law enforcement DNA databases. Due to the DNA technology we have today, authorities have a better chance of solving cases like those of DeAngelo’s victims.

Due to the large number of cold cases in Massachusetts and throughout the country, unfortunately, many of them do not get the chance to be solved. But if everyday citizens help out by talking about cold cases with friends or family, that recognition could help law enforcement solve more cases With the help of witnesses coming forward after years of staying silent, podcasts raising awareness about existing cold cases, and high-tech genealogy databases, we can ensure that murderers are brought to justice and the families of the victims find resolution.